20 Years of Fallout in the Forestry Sector

More than 20 years ago, a tiny insect changed B.C.’s forestry future. The fallout is still happening

Job losses being seen across the province have been predicted for more than a decade, industry leaders say

No one is surprised by the news of Canfor shutting down one of its pulp mills in Prince George.

Not the city’s mayor, not the company, and not the union representing the estimated 300 workers who will be out of a job as a result.

“We knew that at some point, one of these mills was going to shut down,” said Chuck LeBlanc, the Local 9 representative for Canfor Pulp and Paper Mill employees, one day after meeting to announce the cuts.

“Unfortunately, it is our mill.”

Canfor blamed the closure on a reduction in “cost-competitive” fibre available for use at the pulp mill, which takes wood chips and waste from lumber-producing sawmills and turns it into materials used in the production of paper products.

Their workers aren’t alone: over the past few months, hundreds of people across B.C. have been let go as companies announced closures and curtailments, following several years of similar announcements.

Industry analysts say this pattern marks a fundamental shift in B.C.’s forestry future, whose origins can be traced back to a tiny insect more than 20 years ago.

The beetle, climate change and inevitable collapse

Mountain pine beetles were not new to B.C. when they first started making news in the late 1990s.

The insects, as small as a grain of rice, are native to western North America. But at the turn of the century, their population exploded — to devastating effect.

The beetles nest and feed on mature lodgepole pine, once a central part of B.C.’s lumber industry. In the past, their numbers were kept in check by a limited number of trees to feed on, and long, cold winters which would wipe out large portions of their population annually.

But the combination of a warming climate and forest practices that artificially inflated the amount of mature pine available led to an explosion in the insect’s population in northern and central B.C.

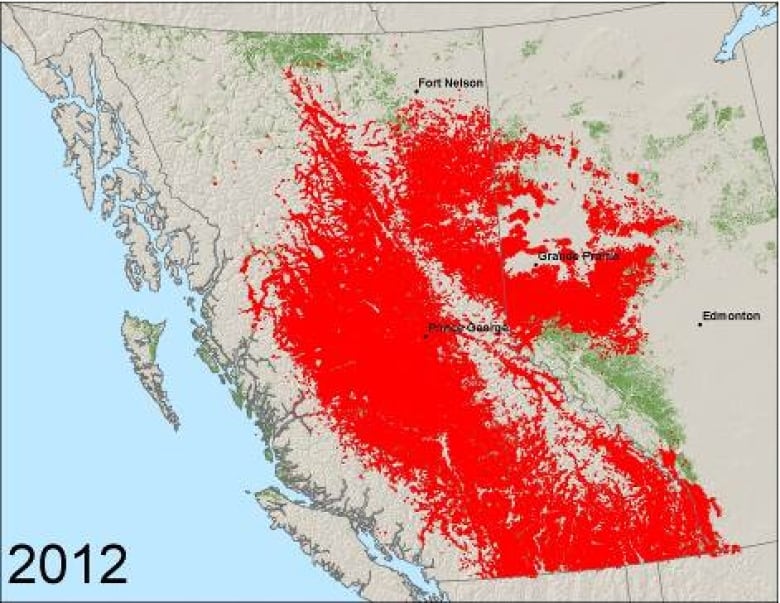

By 2012, more than 18 million hectares of B.C. forest were infested, resulting in the loss of more than half of the province’s merchantable pine.

That did not lead to an immediate downturn in the forest industry, however.

Instead, the government increased the annual allowable cut of forests available to industry, so trees could be harvested before they were no longer viable for the market — an expansion that would lead to an inevitable collapse.

‘We predicted … sawmills would close’: consultant

Sawmills expanded to process the beetle-stricken wood, and for many years, the blue-hued products it created were marketed as a souvenir for visitors to the region.

The change also came with widespread clearcutting in an effort to get to as much pine as possible, a policy that impacted other tree species, as well, along with a rise in raw log exports as the trees were pushed to market elsewhere, and industry consolidation in which smaller companies were absorbed or defeated by a handful of industry giants.

For Bob Simpson, the situation was a ticking time bomb. A former corporate manager for a forests products company, Simpson was elected MLA for the forestry-rich Cariboo region in 2005 before becoming mayor of Quesnel from 2014 to 2022.

His worry was that eventually, the stock of beetle-killed pine would run out, leading to job losses throughout the province.

“My first speech in the legislature … was basically saying this is going to happen,” he said of the mill closures and curtailments happening today.

“I ended up being labeled ‘Chicken Little’ because they thought I was so alarmist.”

But it wasn’t long before his predictions became the standard viewpoint of people in the industry.

“When we first started looking at the whole mountain pine beetle, we predicted [this],” said Russ Taylor, an industry analyst, and consultant.

“We predicted dozens of sawmills would close and that’s exactly what happened.”

A fundamental change in forest economies

Forest fires, the softwood lumber trade dispute with the U.S. and a worldwide recession are also having an effect, as are government policies aimed at protecting habitat for species like endangered mountain caribou.

But Simpson said the idea that B.C. could put off a fundamental shift in the forest industry, as is being seen today, is “magical thinking.”

LeBlanc said as various companies, including Canfor, started announcing sawmill curtailments and closures last year, it became clear pulp mills, which rely on sawmills for raw product, would soon follow.

Prince George Mayor Simon Yu says “the writing was on the wall,” and Joel McKay, CEO of the Prince George-based Northern Development Initiative Trust economic organization, says it has long been accepted as an inevitability that at least one and likely two major pulp mills in the Interior would shut down this decade.

But, he said, Canfor’s decision to permanently shut down a pulp production line is more significant than past sawmill closures because it represents a market that is further upstream from raw forest products — thus a sign of a deeper economic shift.

“I do think that regionally the north really needs to articulate what the vision is going to be for the future and start working on that now because it’s not going to get any easier in the years ahead,” he said.

Provincial shift

John Innes with the forestry department at the University of British Columbia says it’s not just the north that will be affected.

He says forestry is a multi-billion dollar industry that “supports schools, supports First Nations, supports hospitals and other services provided by the government” and that money won’t easily be replaced.

Premier David Eby has acknowledged the need for change in a mandate letter sent to forests minister Bruce Ralston, writing that B.C.’s forest economy has “never been under greater stress.”

He appointed several people, including Simpson, to an advisory council to help transition forestry communities and has asked for a plan to reduce the export of raw logs.

For LeBlanc, this sort of change is long overdue, and he’s disappointed it didn’t already happen under previous NDP Premier John Horgan.

While Eby has pointed to B.C. Liberal-era policies as the root of the problem, people outside of party politics say it’s too simplistic to blame a single party for today’s problems, which are the result of decades of economic, environmental, and policy decisions made at multiple levels.

And while Simpson is glad to see the problem being taken seriously today, he wishes more people had listened nearly two decades ago when he first started raising the alarm.

“We have had a long time to be prepared,” he said.

“We are not.”