Urban-Rural Divide Widens in Sweden

The urban-rural divide is as real in Sweden today as it is in British Columbia, and North America generally.

The Nordic country’s cities continue to grow and develop, while rural communities shrink and unravel. “Young people are moving away, and that carries with it disastrous consequences,” says Charlotte Mellander, professor of national economy at the Jönköping International Business School, in a recent interview with Sveriges Television.

Almost half Sweden’s kommuner (the equivalent of counties or regional districts) have fewer residents today then they did 30 years ago. Many of them are now fighting for their survival., the majority of them rural — since the middle of the 1980s, two-thirds of the country’s rural kommuner have seen their populations steadily decrease.

Energy Loss

It’s especially the young who are moving out of rural areas. With their departure, much of the energy leaches out of small towns and rural regions. “There are fewer folks out shopping, dining out, getting their hair cut, that sort of thing — the sorts of services that make a place attractive, like shops and restaurants, slowly but surely disappear,” says Mellander.

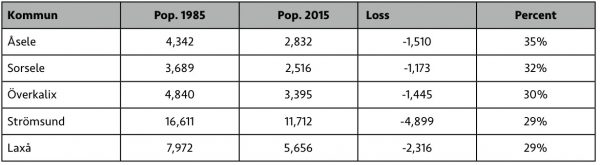

In all, 33 out of the country’s 290 kommuner have lost at least a fifth of their population since 1985. Among the biggest losers are Kramfors, with a loss of over 8,600 residents, Hagfors, down by over 4,700, and Åsele, with its loss of around 1,500 people representing 35 percent of its total population.

Five Swedish Kommun with Greatest Population Loss

“We have a couple bakeries where you can grab a bite, but there isn’t much choice, and what choice there is, is shrinking all the time,” says Linnea Lindberg, a member of the Åsele kommun council. She explains that in Åsele, located in the northern part of the country, in inland Västerbotten, there are individuals and businesses that have to drive over 30 kilometres one way, simply to get the mail.

“We have a couple bakeries where you can grab a bite, but there isn’t much choice, and what choice there is, is shrinking all the time,” says Linnea Lindberg, a member of the Åsele kommun council. She explains that in Åsele, located in the northern part of the country, in inland Västerbotten, there are individuals and businesses that have to drive over 30 kilometres one way, simply to get the mail.

“The big problem is that, as a kommun, we’re required to provide the same level of services as if we were in, for example, Stockholm, despite the fact our tax base is steadily eroding. If we don’t, we’re breaking the law. But what are we going to do the day we can’t balance the books? I don’t know, and that day will soon be upon us,” adds Lindberg.

Rural Angst Leads to Populism

Rural frustration — the sense the Swedish societal deck is stacked against people outside the country’s cities — has led to a growing sense that rural residents are being treated unfairly by “the powers that be,” sowing the seeds of resentful populism.

This frustration is expressed in many ways. Professor Mellander points out that questions such as, “Why don’t we have a police presence here, when we pay more in tax per resident than people who live in Stockholm?” “Why don’t we have bus service?” or “Why isn’t there a school reasonably close to us?” are commonly heard in rural Sweden. In a country where every citizen is supposed to have an equal right to services — a right often not borne out in practice — it’s little wonder rural Swedes are feeling hard done by.

Mellander speculates that part of the problem lies with the inability of city dwellers generally, and urban-based politicians and journalists in particular, to see, to be aware of, to report on the challenges faced by their rural countrymen and women. As a result, people in the countryside feel neglected, misunderstood, and largely abandoned. A general malaise that can lead to feelings of resentment, and even disenfranchisement.

This of course resonates in the North American context. Clearly, the phenomenon of a growing divide between urban and rural — a divide that is at the same time economic, informational, social, cultural, and political — is an international challenge. Our problems are similar — might there be an opportunity to explore common solutions?