The SEED Model for Sustainable Economic Development in Small Rural Towns via Outdoor Recreation

Abstract

1.0 Introduction

2.0 Literature Review

2.1 Challenges for Rural, Remote Communities

According to the United States Census Bureau, the U.S. contains approximately 19,500 incorporated places, roughly 63% of the population. Of those incorporated places, approximately 76% had less than 5,000 residents. Further, about 42% of those had fewer than 500 residents (U.S. Census, 2021). Thus, it becomes clear that we are a nation of small towns. In addition, according to the Center on Rural Innovation (CORI, 2023), about 80% of counties in the United States with long-term persistent poverty are in rural areas. The incidence of poverty is even higher in rural areas with people of colour (CORI, 2023). Furthermore, according to the U.S. Census, about 20% of the population lives in rural areas (United States Census Bureau, 2022). According to the USDA, U.S. poverty rates were almost 30% higher in rural (15.4%) than in urban (11.9%) areas (Dobis et al., 2021). Rural areas in the U.S. have unique challenges, including infrastructure, labour, internet access, health care, and education, among others (Heinrich, 2017). In addition, we suggest that a major reason they cannot overcome poverty and continuing decline is a lack of personnel, resources, and expertise to change their conditions. Given their economic situation, they often have limited budgets to afford the personnel to implement revitalization efforts. This often leads to difficulty

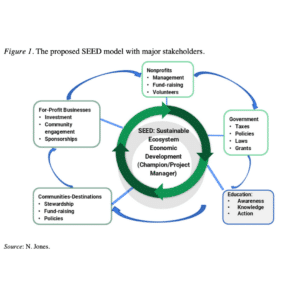

2.2 The Proposed SEED Model with a Focus on the Project Champion as the Key Driver

2.3 The Project Champion in the SEED model

3.0 The Stakeholders

3.1 Government

Local, state, and federal government agencies play a crucial role in helping rural areas with tax incentives, zoning laws, grants, laws, and policies. For example, federal and state agencies can create regulations, standards, and certifications for businesses to improve energy performance and reduce emissions and pollutants. They can provide loans, grants, or tax incentives for investments in renewable energy, waste management, or carbon reduction. Regarding remote, rural economic development, government funding can help with infrastructure investment—roads, broadband, and utilities. In addition, favourable licensing for small businesses, startup grants and loans, and favourable tax policies support nonprofits and communities (Atalla et al., 2022; Macleod, 2023). Government agencies also routinely support communities in the outdoor recreation sector. For example, the Recreation Economy for Rural Communities (RERC) program assists rural communities across the country in improving their outdoor recreation economies, facilitating town revitalization efforts. This is a collaboration between the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), and the Northern Border Regional Commission (NBRC) (USDA, 2022).

3.2 For-Profit Businesses

Small and micro businesses are essential to the health and vitality of rural, remote communities. They provide the preponderance of jobs in these rural areas and are necessary for vibrant communities with businesses like grocery stores, banks, hardware stores, and other essential establishments.

3.3 Nonprofits

3.4 Communities

3.5 Education

Education plays a vital role in this model by building a collaborative shared vision for the goal of sustainable economic development in these remote rural communities. The old phrase that it is bad when “you don’t know what you don’t know” is relevant to education, which provides the information and knowledge needed to implement the SEED Model. Knowledge sharing in the context of education can result in stakeholder commitment and successful implementation (Doten-Snitker et al., 2021).

3.6 Champion/Project Manager

3.7 Ecosystems

3.8 Communication

Again, the project champion represents the crucial element in the SEED model. In addition to boundary spanners to link the disparate stakeholders, someone must be responsible for planning, organizing, implementing, and leading each SEED project.

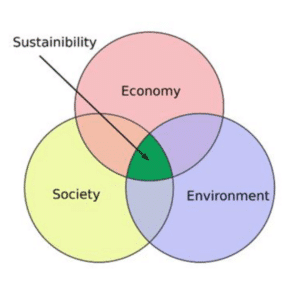

4.0 Sustainable Economic Development

4.1 Basic Concepts

The sustainable development concept was adjusted to fit the existing frameworks of various academic fields. In the business literature, the sustainable development paradigm was realized in the sustainable business model (SBM) (Schalteggeret al.,2016) and the idea of the triple bottom line(Elkington,1997). The paradigm was employed in the public policy literature to model government policy. (Hull,2004). The list continues. These discipline-focused iterations of sustainable development acknowledge the roles played by entities outside the scope of their respective fields, e.g., the role of stakeholders in SBMs (e.g., Fobbe &Hilletofth, 2021) as well as the role of local governments (Kim &Chan, 2023). This infers the need for an integrated, interdisciplinary approach to sustainable economic development.

4.2 Integration of Sustainability into the SEED Model

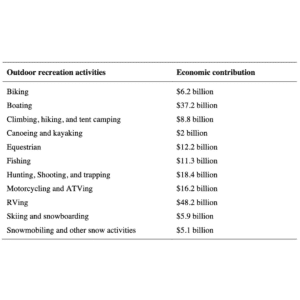

4.3 Role of Outdoor Recreation as a Driver of Sustainable Economic Development

According to IBIS World (Dalal, 2023), continued increased demand for natural experiences in an environmentally friendly way represents increasing demand for outdoor recreation. Their research suggests that for-profit businesses rely on partnerships with nonprofits and government entities to create sustainable experiences. This infers the involvement and collaboration with local communities.

4.4 Possible Challenges of the SEED ModelRelated to Nature-Based Tourism/Outdoor Recreation

- Communities of colour are three times more likely than white communities to live in nature-deprived places. Seventy-four percent of communities of colour in the contiguous United States live in nature-deprived areas, compared with just 23 percent of white communities(p. 1).

- Seventy percent of low-income communities across the country are located in nature-deprived areas. This figure is 20 percent higher than those with moderate or high incomes(p. 1).

- Nature destruction has had the largest impact on low-income communities of colour. More than 76 percent of people who live in low-income communities of colour live in nature-deprived places(p. 2).

5.0 Test Pilot of The SEED Model

5.1 Trade Mission Learning Trip

- A Baroness in the House of Lords, Environment and Climate Change Committee Chair. She focused on developing collaborations with other government agencies (national, regional, and local) and local communities to understand the impacts of climate change and sustainability on communities, including their economic health and revitalization.

- 40-year expert with the U.S. Department of Commerce. He focused on helping communities, including small towns and regions, understand how to leverage their natural resources/outdoor recreation to bring visitors in and potentially people who would want to move there. The goal was to increase revenues to the areas and assist with economic development.

- General manager for Hardy Fishing: During this visit, we learned the power of brand development as it relates to the outdoor industry.

- President and founder of Stoats Oats: This sustainable oat-based food company showcases how a small business can use sustainable practices to help mitigate climate change and leverage sustainability for competitive advantage.

- Marketing manager of St. Andrews Golf Course: shared best practices for community engagement to preserve the cultural identity of a small rural town while helping to use St. Andrew’s iconic brand to contribute to community economic sustainability.

- Tomatin Whisky Distillery manager shared experiences of working collaboratively with the local community to preserve a successful symbiotic relationship with citizens and visitors.

- Chairof the Outdoor Access Trust for Scotland (OATS): shared gold-standard practices in communities in the Scottish Highlands to develop outdoor recreational areas in sustainable ways while creating healthy, thriving communities that had been in decline.

5.2 Lessons Learned

- Successful collaboration among important entities includes government agencies at all levels in a country.

- Engagement and commitment by local communities that interact with government agencies and nonprofits create successful ecosystems for economic development.

- Collaborations with for-profit businesses similarly develop synergies with the local communities by leveraging their well-known brands and resources.

6.0 Test Pilot Project

6.1 Background

6.2 Success Factors

6.3 Implementation

7.0 Discussion and Conclusions

Our pilot project suggests that the SEED model with the project champion plays a vital role in the success of small rural town revitalization.

8.0 Limitations and Future Research

References