Rural Hospice and Palliative Care Models and Innovations

This report features three rural hospice and palliative care model programs and successful rural projects in the U.S. that can serve as a source of ideas, and provide lessons others have learned for practitioners and rural community-based organizations in British Columbia, and elsewhere in rural Canada.

Project ENABLE (Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends)

Summary

- Need: To enhance palliative care access to rural patients with advanced cancer or heart failure and their family caregivers.

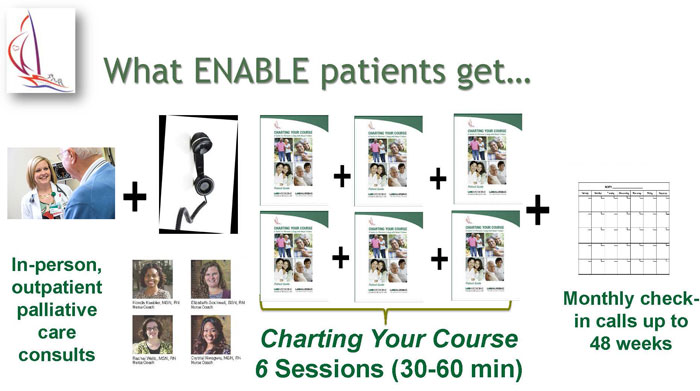

- Intervention: Project ENABLE consists of: 1) an initial in-person palliative care consultation with a specialty-trained provider and 2) a semi-structured series of weekly, phone-delivered, nurse-led coaching sessions designed to help patients and their caregivers enhance their problem-solving, symptom management, and coping skills.

- Results: Patients and caregivers report lower rates of depression and burden along with higher quality of life.

Description

Palliative care is often limited in resource-scarce rural communities. While palliative care has traditionally been offered only after exhausting curative treatment options, a growing number of clinical trials demonstrate that offering palliative care at the time of diagnosis and concurrent with disease-oriented care can help improve patients’ symptoms, quality of life and mood, and help them and their caregivers plan for an unpredictable future.

Palliative care is often limited in resource-scarce rural communities. While palliative care has traditionally been offered only after exhausting curative treatment options, a growing number of clinical trials demonstrate that offering palliative care at the time of diagnosis and concurrent with disease-oriented care can help improve patients’ symptoms, quality of life and mood, and help them and their caregivers plan for an unpredictable future.

Project ENABLE (Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends) is a telehealth approach that provides palliative care to patients with serious illnesses and their family caregivers. ENABLE was developed in rural New Hampshire and Vermont and is now being implemented and tested in the southeastern United States and in selected areas of Honduras, Turkey, and Singapore.

History of Project ENABLE

Project ENABLE I (1998-2001) was developed through a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation-funded demonstration project involving 380 patients at three northern New Hampshire cancer practices: the Norris Cotton Cancer Center (NCCC) at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in rural Lebanon, Oncology Associates in Manchester, and a Critical Access Hospital in rural Berlin. The goals were to provide a supportive care intervention to patients who were newly diagnosed with advanced cancer and had limited access to palliative care.

A nurse coach met with patients to facilitate a 4-session seminar guided by the Charting Your Course guidebook, which helps patients and families better cope with their physical, functional, emotional, and spiritual needs. The nurse coach also coordinated care between the cancer centres and their communities. Family caregivers were invited but not required to attend. If they were interested but unable to attend in person, nurse coaches provided the content to patients and families over the phone.

ENABLE II (2003-2008) was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Building on ENABLE I, including adapting the in-person intervention to one delivered by phone, the study’s aim was to evaluate the efficacy of ENABLE to improve quality of life, symptoms, and mood for patients with advanced cancer compared to standard care. Over 300 patients enrolled over 4 years: Half of the patients received ENABLE and half received usual cancer care. Family caregivers did not receive a specific intervention but were invited to participate in patients’ in-person palliative care consultations.

ENABLE III (2010-2013), funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), was an RCT examining the timing of providing ENABLE to patients and a parallel intervention for family caregivers. Patients and their caregivers were randomly assigned to receive the intervention immediately or 12 weeks after enrolment. The intervention included an in-person comprehensive assessment by a palliative care-certified clinician followed by nurse coach-delivered telehealth sessions. (Patients received 6 sessions and caregivers received 3 sessions.) The patient and caregiver each had a different nurse so that each participant could share questions or concerns freely. Nurses maintained monthly contact with patients and caregivers after the sessions were completed.

ENABLE IV (2012-2017), funded by the American Cancer Society, was an implementation science study using a virtual learning collaborative (VLC) approach to implement ENABLE at racially diverse, rural-serving community cancer centres in Alabama and South Carolina. ENABLE implementation teams at each site were supported by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Coordinating Center experts via monthly videoconferences and annual site visits. Site teams reported monthly progress, patient experience, implementation costs, and lessons learned.

ENABLE CHF-PC (Comprehensive Heartcare for Patients and Caregivers: 2010-present), funded by Dartmouth SYNERGY and the National Palliative Care Research Center Pilot awards, adapted ENABLE to also serve patients with heart failure and their family caregivers. A full-scale efficacy RCT is enrolling patients and caregiver participants across the Deep South. ENABLE CHF-PC combines an in-person palliative consultation by a palliative care specialist and weekly nurse coach telehealth sessions (6 for patients and 4 for caregivers) and monthly follow-up. The sessions also follow “Charting Your Course” and services are tailored to meet a patient’s and family’s unique needs.

Current efforts are focusing on tailoring this early palliative care approach further for cancer family caregivers (ENABLE-CORNERSTONE) and for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and family caregivers (early palliative care for COPD-EPIC).

Services offered

Nurse coaches provide Charting Your Course sessions for patients and caregivers. These sessions cover topics such as symptom management, self-care, decision-making, and advance care planning. While palliative care services are considered standardized, they can be tailored to meet the individual patient’s and caregiver’s needs.

Results

ENABLE I:

- Compared to national and regional data, a larger number of participants in ENABLE died in their preferred site. (For many participants, this meant dying in their own home.)

- A higher percentage of ENABLE family members reported that the patient and providers worked to ensure that patient preferences for medical treatment were followed.

ENABLE II:

- Intervention patients reported lower depressed mood and higher quality of life, with trends toward improved symptom management and survival.

- ENABLE was listed as a Research-Tested Intervention Program (RTIP) by the National Cancer Institute.

ENABLE III:

- Kaplan-Meier survival rates one year after enrolment were 63% for those in the early intervention group, compared to 48% for those who began intervention 3 months later.

- Caregivers in the early intervention group had lower depression and stress burden scores.

- The American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) identified ENABLE as one of the year’s greatest advances in clinical cancer care.

ENABLE IV:

- Program coordinators developed and tested the ENABLE Implementation Toolkit to assess pre- and post-implementation success.

- They demonstrated feasibility of using a VLC strategy to implement ENABLE in non-academic, community-based cancer practices that serve a high proportion of rural, minority cancer patients and their family caregivers.

ENABLE CHF-PC:

- Results of a pilot study demonstrated feasibility of carrying out ENABLE with 61 patients and 48 caregivers in New England and the Southeast.

- Patients and caregivers experienced moderate improvements in quality of life and mental health. Patients’ symptoms and physical health as well as caregivers’ burden improved.

Barriers

Patient barriers include poverty and unemployment, level of education, mistrust of healthcare, travel to care, and insulated communities.

Provider barriers include lack of palliative care education, experience, and expertise.

Policy/system barriers include inability of small cancer centres and practices to support palliative care expertise and disincentives from limited reimbursement.

Replication

Early lessons learned from the implementation study include:

- The importance of administrative and palliative care leadership buy-in, support, and commitment

- The need for oncologist champions

- Protected time for coaches to deliver the program

- The need for strategically incorporating ENABLE model elements into existing work-flow patterns

- A referral trigger that does not rely solely on oncologist referral

Contact Information

Dr. Marie Bakitas, Professor and Marie L. O’Koren Endowed Chair / Associate Director

University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Nursing / UAB Center for Palliative and Supportive Care

UAB Center for Palliative and Supportive Care

205.934.5277

mbakitas@uab.edu

Care for Our Elders/Wakanki Ewastepikte

Summary

- Need: To provide Lakota elders with tools and opportunities for advance care planning.

- Intervention: An outreach program in South Dakota helps Lakota elders with advance care planning and wills by providing bilingual brochures and advance directive coaches.

- Results: Care for Our Elders saw an increase in the number of Lakota elders understanding the differences between a will and a living will and the need to have end-of-life discussions with family and healthcare providers.

Description

In the U.S., more than other ethnic groups, American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian elders tend to have poorer health, less money, greater disability, and shorter life expectancies. In South Dakota, 12.2% of the American Indian population has diabetes, compared to the Caucasian population with a diabetes rate of 6%. According to a 2013 American Journal of Preventive Medicine article, American Indians in South Dakota have the highest mortality rates in the nation, with heart disease and cancer as the leading causes of death.

Elders seeking medical attention often experience cultural barriers. For example, while many Lakota elders are fluent in English, their healthcare providers often don’t speak Lakota or ask if patients would like a translator. If patients have to hear bad news, for example, they might prefer to hear it in their native language, since they don’t have to mentally translate the doctor’s words into Lakota first. Speaking and listening in Lakota becomes more personal, and the elders are better able to deal with the news.

In addition, the Lakota people, among other tribes, do not view property or wealth the same way Caucasians often do. While Lakota elders may not see a need for a legal will explaining who will inherit what, their property will still be divided or transferred by the government.

Care for Our Elders began when a palliative care physician asked Assistant Professor Mary Isaacson from South Dakota State University and her nursing students why American Indians from the western side of the state were traveling to Sioux Falls to receive palliative care and hospice care, when the majority of reservations are located in western South Dakota. This group met with healthcare, palliative care, and hospice care providers to discuss why this was the case. Many providers said that they were hesitant to broach the subject with their older patients, in case the suggestion of hospice care might be interpreted as the providers giving up on their patients.

However, when this group discussed palliative and hospice care with Lakota healthcare professionals in the region, they explained, “No, this is something we need.” Isaacson then met with Lakota elders and discussed how palliative and hospice care might work on the reservations and what the elders wanted from those programs. The elders saw death not as giving up, but as another cycle of life.

Care for Our Elders collaborates with local organizations and branches such as the Oglala Sioux Tribe Health Administration, Oglala Sioux Tribe Health Education, Dakota Plains Legal Services, and Indian Health Service in order to increase awareness of the need for advance care planning by American Indian elders in South Dakota.

The program was initially funded by a $2,500 Delores Dawley Faculty Seed grant and is now supported by a $10,000 grant from the South Dakota Cancer Coalition.

Services offered

Three Pine Ridge Reservation elders received training to become advance directive coaches. The program has found that the other Lakota elders are more receptive to coaches from their culture than to coaches from outside their culture. These coaches:

- Delivered Public Service Announcements on the local radio station

- Developed a 30-minute informational television program with the Oglala Lakota College media personnel

- Traveled to community centres and health fairs around the Pine Ridge Reservation to inform fellow elders about their palliative care and end-of-life options and resources.

In addition, the advance directive coaches and Isaacson designed a new advance directive brochure. This brochure, illustrated by a Lakota artist, translates key terms into Lakota and medical jargon into everyday language. Social workers and nurses use the brochures to talk elders through the steps and the importance of choosing a Healthcare Decision Maker. In addition, the brochure provides the names of Indian Country partners and the contact information for Dakota Plains Legal Services.

In turn, Dakota Plains Legal Services provides free services to any Lakota elder aged 62 or older and will drive to any community where at least four individuals are requesting their services. For Pine Ridge, a reservation that encompasses over 2 million acres, Dakota Plains’ offer can provide immense relief to elders without transportation.

Results

Since the program’s inception, the three advance directive coaches have traveled over 1,000 miles, visiting 11 different communities and completing 229 face-to-face contacts. The advance directive coaches completed contact sheets, which asked elders whether they had ever heard of palliative care or whether they had heard of or had a living will.

Before Care for Our Elders, 84% of those surveyed had never heard of a living will, and only 1 of the 229 elders actually had a living will. None of those surveyed had heard of palliative care. Thanks to the program, more Lakota elders understand the differences between a will and a living will as well as the need to have end-of-life discussions with family and healthcare providers.

For more information about program results:

Isaacson, M. (2017). Wakanki Ewastepikte: An Advance Directive Education Project with American Indian Elders. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 19(6), 580-587.

Barriers

Implementing Care for Our Elders took longer than anticipated. The advance directive coaches and Isaacson went through the Oglala Sioux Tribal Research Review Board (OSTRRB) and had to start their educational program two months later than planned. Since this step was important to the group, they simply readjusted their schedule and began the educational programs that included some data collecting in mid-August instead of June. Due to changes within health administration, the group needed to present their proposal again so that the new staff was aware of the program.

Other barriers in carrying out the program include the immense size of the reservation and weather conditions that prevent program coordinators and participants from traveling.

Replication

Healthcare providers working with patients from other cultures need to move from broad generalizations about a culture to more specific information about a group or patient within that culture. Isaacson, for example, might read about Native American health issues but then speak with the spiritual healer or medicine man in a specific Lakota tribe. She asks how she can best approach a subject like Alzheimer’s with a patient. When she meets with a patient, she invites the elder to bring family members and other support.

Providers should also be willing to take on the role of facilitator or encourager and leave the role of doer to the elders. Care for Our Elders works because it stems from what the elders want and need, not from what others want for them.

In addition, program coordinators recommend involving the community every step of the way. Letting the community lead the program helps to ensure that it is done in the most culturally respectful way possible.

The advance directive brochure is now available via the South Dakota Department of Health educational materials catalog and can be downloaded or ordered free of charge. The brochure is not copyrighted, so any group can borrow, use, or distribute the brochures and change whatever they need to in order to make the brochures specific to their targeted audience.

For those who want to train advance directive coaches or do advance directive education, the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization offers useful information in plain language. Isaacson used information from this and other websites to create packets for the advance directive coaches. They talked through the information together, and the advance directive coaches were able to keep the packets for future reference.

Contact Information

Mary Isaacson, Assistant Professor

South Dakota State University, College of Nursing

605.367.8308

mary.isaacson@sdstate.edu

Care Partners of Cook County

Summary

- Need: To provide holistic, interdisciplinary palliative care to those with chronic illnesses in rural hospitals in Cook County, Minnesota.

- Intervention: Care Partners of Cook County created a palliative care program that utilizes local healthcare professionals and volunteers to provide universal care to patients and caregivers, without Medicare hospice status.

- Results: Since its inception in 2010, the program has assisted over 185 residents in need.

Description

Because most care options focusing on palliative treatment of chronic and debilitating illnesses in Minnesota are available only in a hospital setting, Care Partners of Cook County was created to address the lack of hospice and palliative care options for the rural residents in this Minnesota county.

Because most care options focusing on palliative treatment of chronic and debilitating illnesses in Minnesota are available only in a hospital setting, Care Partners of Cook County was created to address the lack of hospice and palliative care options for the rural residents in this Minnesota county.

Urban areas have large patient volumes to support palliative and hospice care programs. But due to Cook County’s location 110 miles from the nearest tertiary centre, the area was unable to offer round-the-clock continuous home care, which prevented the program from meeting Medicare’s hospice regulations.

In 2010, Care Partners of Cook County was created by a Community Service/Community Services Development grant from the Minnesota Department of Human Services to meet patient needs despite these challenges. The program was also the result of strategic partnerships with North Shore Health Care Foundation and Sawtooth Mountain Clinic.

This program is unique because it not only connects patients with medical services, but connects them to community services such as transportation, meals, and financial services. Care Partners engages professionals and volunteers to lend emotional and spiritual support, hand-in-hand with providing physical relief. Local physicians, nurses, social workers, and volunteers coordinate holistic, suitable care options for patients and caregivers through a team approach to palliative care.

A physician and local nurse coordinator conduct monthly review for program patients, ensuring that patient needs are being met, symptoms are being managed, and medications and treatments are working properly. By involving social workers and volunteers, the program also helps caregivers of patients with chronic illnesses. These caregivers are offered coaching, emotional support, and resource coordination. Trained volunteers are available to provide companionship and assist with patient activities. This program’s community-based approach provides personalized care to the patients in Cook County, without having to leave the comfort of their homes.

Services offered

- Palliative care coordination

- Caregiver coaching and support

- Resource coordination

- Advanced care planning

- Senior rides service

- Training, education, and public programs

- Volunteer visits

- Senior Chore Program

Results

Since its inception in 2010, Care Partners of Cook County has served 185 residents seeking palliative care. In 2015, Care Partners of Cook County became an independent 501(c)3 nonprofit organization.

Summary of 2016 services:

- Served 119 clients

- 42 Senior Ride clients received nearly 380 rides

- 34 clients received 178 Care Coordination/End-of-life care hours

- 24 clients received 174 Volunteer Visits

- Volunteer drivers logged over 11,000 miles

- More than 400 hours of coaching and support for 36 caregivers

Barriers

The main challenges surrounding this program are:

- Shortages of volunteers willing to donate extended periods of time

- Connecting with clients before they reach a crisis mode

- Low program enrolment due to the small size of the community

Replication

In order to make this model most helpful, communities should do the following:

- Adapt each person’s need to the variety of services available

- Establish a care coordinator and system of volunteers

- Build relationships with local healthcare professionals

Contact Information

Kay Grindland, Director

Care Partners of Cook County

218.387.3788

carepartners@boreal.org

Bibliography

Bakitas, M.A. (2017). On the Road Less Traveled: Journey of an Oncology Palliative Care Researcher. Oncology Nursing Forum, 44(1), 87-95. Article Abstract

Bakitas, M.A., Elk, R., Astin, M., Ceronsky, L., Clifford, K.N., Dionne-Odom, J.N., … & Smith, T. (2015). Systematic Review of Palliative Care in the Rural Setting. Cancer Control, 22(4), 450-464. Article Abstract

Bakitas, M.A., Tosteson, T.D., Li, Z., Lyons, K.D., Hull, J.G., Li, Z., … & Ahles, T.A. (2015). Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(13), 1438-1445.

Dionne-Odom, J.N., Azuero, A., Lyons, K.D., Hull, J.G., Tosteson, T., Li, Z., … & Bakitas, M.A. (2015). Benefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care to Informal Family Caregivers of Patients with Advanced Cancer: Outcomes from the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(13). 1446-1452.

Dionne-Odom, J.N., Kono, A., Frost, J., Jackson, L., Ellis, D., Ahmed, A., … & Bakitas, M. (2014). Translating and Testing the ENABLE: CHF-PC Concurrent Palliative Care Model for Older Adults with Heart Failure and Their Family Caregivers. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(9), 995-1004.

Bakitas, M., Lyons, K.D., Hegel, M.T., & Ahles, T. (2013). Oncologists’ Perspectives on Concurrent Palliative Care in a National Cancer Institute-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. Palliative & Supportive Care, 11(5), 415-423. Article Abstract

Maloney, C., Lyons, K., Li, Z., Hegel, M., Ahles, T.A., & Bakitas, M. (2012). Patient Perspectives on Participation in the ENABLE II Randomized Controlled Trial of a Concurrent Oncology Palliative Care Intervention: Benefits and Burdens. Palliative Care, 27(4), 375-383.

O’Hara, R.E., Hull, J.G., Lyons, K.D., Bakitas, M., Hegel, M.T., Li, Z., & Ahles, T.A. (2010). Impact on Caregiver Burden of a Patient-Focused Palliative Care Intervention for Patients with Advanced Cancer. Palliative & Supportive Care, 8(4), 395-404.

Bakitas, M.A., Lyons, K., Hegel, M., Balan, S., Brokaw, F., Byock, I., … & Ahles, T. (2009). Effects of a Palliative Care Intervention on Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Advanced Cancer: The Project ENABLE II Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 302(7), 741-749.

Bakitas, M., Stevens, M., Ahles, T.A., Kirn, M., Skalla, K., Kane, N., & Greenberg, E.R. (for Project ENABLE staff). (2004). Project ENABLE: A Palliative Care Demonstration Project for Advanced Cancer Patients in 3 Settings: One Project of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s “Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care.”Journal of Palliative Medicine, 7(2), 363-372. Article Abstract

For more information on rural healthcare issues, visit our Health page.