Rural Health Initiatives in BC

Introduction

Providing adequate — let alone excellent — health care in rural and remote BC communities, regions, and First Nations presents a set of unique challenges, including vast distances, lack of transportation infrastructure, staffing difficulties, scattered populations, poor or no bandwidth, and a range of socio-economic conditions that impact on health and well-being.

In this brief report, we will showcase a number of initiatives that attempt to tackles some of these challenges, in the process suggesting ways rural BC health care may improve going forward.

From Telehealth to CODI

Dr. John Pawlovich, a family physician living in Abbotsford, BC, has a thriving practice in Takla Landing, a rural and remote aboriginal community located approximately 400 km north of Prince George. Like many physicians providing rural and remote healthcare, he flies or drives by 4X4 into Takla Landing once a month for a week to meet face-to-face with patients. Unlike many physicians, however, Pawlovich for some years now has regularly met with and examined these patients, and consults with Takla Landing clinic nursing staff on a daily basis from his home office via videoconference for the other three weeks of the month.

Pawlovich and Takla Landing were part of a pilot project initiated in 2013 by Carrier Sekani Family Services to explore how telehealth technologies could be used to provide primary care support to isolated aboriginal communities. The project, which started in 2010, was an unmitigated success. After installing state-of-the-art videoconferencing equipment that included peripheral examination tools such as a stethoscope, an ENT camera, and a general exam camera, the Takla Landing healthcare team developed processes and competencies to integrate the new technology into their daily services.

Telehealth enabled nurses and physicians who were off-site to collaborate in an unconventional manner. Nurses often lead much of the care at Takla Landing, and used the telehealth system to consult with Pawlovich via iPad, smartphone, or HD desktop screen and camera when a complex health issue requirds a consult. Caroline Alger, an RN who has worked at Takla Landing, notes that it is amazing to have a physician listen via telehealth to heart, lung, and bowel sounds, examine wounds, and talk to the patient to explain their symptoms and diagnosis. “It takes away the guesswork that occurs when a physician prescribes on the basis of the examining nurse’s description of symptoms and findings,” says Alger, and she notes that telehealth also helped her learn new skills and review existing competencies in patient examination and treatment. Support of healthcare services through telehealth enabled care workers to manage more patients in-community, and reduced the number of patient transfers to acute care facilities elsewhere, saving money and reducing patient stress.

In addition to enhancing acute healthcare provision, telehealth also enabled much more optimal management of chronic diseases, allowing patients to receive proactive and preventative care from a familiar healthcare provider. “The ability to continue to directly work with a patient despite not being physically present in the community is a game changer,” says Pawlovich.

The success of the Takla Landing pilot project led to further investigation about the effectiveness of telehealth in supporting specialist care. “We’re now offering several specialties within Takla Landing, including general surgery, thoracic surgery, infectious disease care, nephrology, addictions, HIV and AIDS, dermatology, and cardiology,” notes Pawlovich. While complex treatments may not take place at the community health clinic, local healthcare staff and telehealth have both played a key role in managing and supporting patients. For example, Pawlovich and clinic nurses managed simple surgical pre- and post-operative exams in-community by videoconferencing with the specialist.

The First Nations Health Authority, interested in the outcomes of the Takla Landing pilot project, initiated a Telehealth Expansion Projectof its own, launching near the end of 2013. This project was intended to create the opportunity for a large number of aboriginal communities to get involved with telehealth when they were able and ready to do so.

Pawlovich is cautious about referring to telehealth as a cure-all for addressing gaps in aboriginal health. He notes that communities should assess what services are currently available and explore how telehealth will be able to improve those services. “You need to have a model of service delivery before you can bring in telehealth equipment,” he observes. “If there is no care available in the community, the technology won’t be able to miraculously create it.”

There were and remain other challenges facing remote and rural aboriginal communities wishing to augment their healthcare programs with telehealth technologies. Telehealth is heavily reliant on internet connectivity, and requires a great deal of bandwidth to function properly. In regions of BC that do not have access to high speed connectivity, acquiring this bandwidth (usually through satellite internet connections) can be difficult and costly. Video conferencing equipment, too, can also be expensive. However, Pawlovich was confident, “way back” in 2013, that the rapid evolution of mobile technologies would likely bring such barriers down over time — a confidence that was to prove well-founded six years later.

Takla Landing residents have embraced new technology in a brave and collaborative manner, and remain at the forefront of a new, emerging paradigm of healthcare. Six years ago, Pawlovich speculated that in the future, all patients would have the ability to access their healthcare provider virtually, and that virtual care would complement in-person care for remote and rural patients. Web-based delivery of healthcare and telehealth would significantly impact overall access to and cost of healthcare, physician licensure, and billing – issues which in 2013 had not yet been examined. Pawlovich added, “Telehealth is going to lead us into areas we can’t imagine presently. It wasn’t that long ago that the local Takla Landing care aid was calling for urgent help over a VHF radio. Now with the click of a mouse, the physician arrives at the bedside. Stay tuned!”

Which brings us to CODI.

The rural and remote emergency room (ER) remains one of the leading health care challenges in Canada and around the world. Geographic and human isolation, low resources, climate, daily anxiety and fear, fatigue, minimal specialist back up, etc., are just a few of the obstacles that relentlessly erode the spirit and confidence of rural physicians. For many, the mountain to scale to achieve a successful and enjoyable career in rural medicine is often the rural emergency room.

In 2017, Pawlovich met with fellow physician, Don Burke, at the BC Rural Healthcare Conference in Prince George, while presenting on telehealth & remote medicine, and critical care, respectively. Out of this initial chance encounter spawned an idea to support physicians in rural and remote BC in a new and exciting way: provide physicians with timely access to kind, knowledgeable, and collaborative assistance at the point-of-care for the most critically ill patients. The seed for CODI (Critical Outreach and Diagnostic Intervention) was sown.

Together with Dave Loewen and Jeff Harder representing the technical side, CODI was born. CODI is a secure iOS smartphone app that is an integration of technology and the “right people” to support rural providers during stressful and challenging times in the emergency room. Literally, it is an on-demand, 24/7 “intensivist in your pocket” that can directly connect a rural physician to an intensivist, using technology similar to a FaceTime call. CODI’s simplicity makes it powerful: through the touch of a button on a familiar device, people are connected in real time to work together through complex, intimidating, and anxiety-filled situations. Virtual critical care consults are dictated and sent on for transcription using the secure app. Medical reports flow back to the rural physician in an extremely timely fashion for integration into the patient’s chart. CODI specialists are selected for their knowledge and skill, compassion and empathy, rural awareness, and willingness to help.

Through this easy connection of humans, anxiety is lessened, physicians and nurses are empowered, and most importantly, patients gain an exceptional level of care. CODI raises everyone’s game in the rural emergency room. Moreover, through this collaborative care process, value-added benefits such as education start to be possible. Bedside review of sepsis management, need for intubation, chest tube insertion or central line insertion are just some examples of clinical presentations that can be taught on-the-fly. The rural emergency room in Canada has never seen anything like CODI – this blend of technology and the right people has created a BC-developed care strategy that is truly transformative.

While the technology is impressive, it is the human element of CODI that will likely provide the greatest positive impact on rural healthcare. Chronic stress undermines the community life expectancy of a rural and remote physician. It is plausible that CODI’s virtual, 24/7 presence in the pocket of a physician will lessen anxiety, build confidence, enhance quality of life, and positively impact recruitment and retention in rural and remote BC (and ultimately, all of Canada). Enhanced patient outcomes and reduced out-of-community transfers are other potentially positive outcomes of CODI.

To date, over 200 rural providers have signed up for CODI. The next phase for CODI will be the addition of CODI-EM (Emergency Medicine). This second phase will allow rural providers to reach out for immediate support on cases proving to be a challenge in the emergency room, both critical and non-critical. An all-encompassing EM support strategy could prove beneficial to vulnerable providers in the rural setting (young graduates, International Medical Graduates, Practice Ready Assessment physicians, those returning to rural practice after a long absence, etc.).

CODI is proving to be the most transformative blend of technology and people the rural emergency room has ever seen, with rural colleagues articulating that CODI should be the “Standard of Care.” Time and evaluation will determine the true positive outcomes of CODI, as there is clearly a domino effect in smaller communities when healthcare in empowered and doctors are truly supported. Although it is early, CODI is making a difference.

There is little question that telehealth, in its various forms, can make a substantial difference in the quality of healthcare available to residents of rural, remote communities, and First Nations across BC, as these next two videos illustrate.

Irene Williams is a Community Health Representative who facilitates meetings between physicians, nurses, and patients in the community of Tachet.

Dr. Terri Aldred is a First Nations physician who overcame personal challenges to come back to her people from the community of Tachet, Lake Babine Nation in Northern BC, to deliver exceptional healthcare using Telehealth.

The Rural Evidence Review

The Rural Evidence Review (RER) project is a four-year initiative, jointly funded by the Rural Coordination Centre of B.C. and Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research. The project aims to work in collaboration with rural patients and community stakeholders to provide robust, comprehensive, and rural-relevant evidence to inform rural health services planning in British Columbia. The activities involved to achieve this goal include:

- engaging rural citizen-patients in B.C. to identify their rural health service priorities;

- synthesizing the international evidence on stated priorities;

- promoting the uptake and use of the evidence into policy and planning discussions in the province.

Past issues and priorities that the RER has reviewed include community-led initiatives and strategies for the recruitment and retention of health care providers to rural and remote communities, and the willingness of urban patients to travel to rural areas for elective surgical care. The RER project’s current review explores community participation in health services planning and decision-making via boards of health.

To learn about rural citizen and community priorities for health services, the research team developed a survey that is publicly available via the project’s webpage. The anonymous survey – which can be completed in 10 minutes or less – serves as a way for the RER team to communicate with rural B.C. community members about health service issues and priorities.

The RER’s goal is to learn from as many rural community members as possible about the health service issues that are most important to them and their communities. The information gathered from the survey responses helps to ensure the project answers the questions that matter the most to rural citizen-patients, and generates evidence that is relevant, appropriate, and useful for rural communities across the province.

The survey tool is not the only form of outreach the RER team uses to engage with rural patients and community representatives. Christine Carthew, the project’s Coordinator, stresses, “We welcome phone calls and emails too, either in addition to or instead of the survey. We want to connect with as many people as possible, in whatever way they are most comfortable to discuss their rural health care priorities.”

To learn more about the Rural Evidence Review project, or to speak with the Project Coordinator about the health care priorities that matter the most to your rural community, visit the project’s webpage, call 604-827-2193, or email Christine at christine.carthew@ubc.ca.

Or, click here to complete the RER’s brief and anonymous survey.

Gabriola Islanders Make a Healthy Choice

The community of Gabriola Island was selected for the Rural Coordination Centre of BC’s 2018 BC Rural Community Award at the BC Rural Health Conference in Nanaimo, BC, on May 12, 2018.

The community was honoured for its innovation and resiliency in recovering from a healthcare crisis in 2006, when one of the island’s physicians – frustrated by a lack of medical facilities and services – nearly left.

The community addressed the situation by creating the volunteer-led Gabriola Health Care Foundation (GHCF), which organized funding and recruitment of volunteer labour to build a 8,500 sq. ft. health centre.

The community health centre opened its doors in 2012.

Brenda Fowler, former President of the GHCF and member of the Gabriola Health and Wellness Collaborative, said, “The Health and Wellness Collaborative on Gabriola has taken the engagement of the building of the Community Health Clinic and refocused that effort into preventative programs across our community. By working together we have been able to raise awareness about steps we can all take to be more active, keep socially connected and make healthy food choices.”

Dr. Tracey Thorne said, ““We, the doctors, Brenda, and Nancy Rowan, were there to accept the award, but this was an award for the entire community of Gabriola.”

Today, the Community Health Centre provides access to three family doctors, emergency care, a helipad for medical evacuations, a mental health nurse, home care nursing, two social workers (community and seniors outreach), a visiting psychiatrist, surgeon, and plastic surgeon, home support workers, a medical lab, a dental clinic, and telehealth.

Since the opening of the clinic, the community formed the Gabriola Health and Wellness Collaborative, a dedicated group of volunteers who identify and work to improve social determinants of health. During its first year, the Collaborative focused on the mental health and substance use issues and partnered with the Canadian Mental Health Association and University of Victoria to train dozens of community members in Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. In 2018, the Collaborative will address supports for child poverty and hospice services.

Dr. Ray Markham, Executive Director of the Rural Coordination Centre of BC (RCCbc) said the organization, “is pleased to recognize the pivotal role of rural communities in supporting the recruitment and retention of rural healthcare providers. Gabriola Island is a shining example of how grassroots efforts and passion can create substantive change.”

2018 marks the fifth year that RCCbc has recognized BC physicians and communities for their contribution and dedication to rural medical practice with the BC Rural Health Awards (formerly the Awards of Excellence in Rural Medicine). Each year, RCCbc recognizes rural physicians within a themed category (e.g., Rural Opinion Leaders in 2015, Outstanding Mentors in 2014) as well as acknowledging long-term practitioners who have shaped and served their communities for more than 15 years. In 2016, RCCbc began to honour the valuable work of inter-professional health care teams in sustaining and/or retaining rural community health services in British Columbia.

Recipients were selected by a committee consisting of representatives from RCCbc and the University of British Columbia. All award recipients receive a plaque, along with a $2,500 grant to be used for hosting a community celebration.

The BC Rural Health Awards are made possible through the generous funding provided by the Joint Standing Committee on Rural Issues (JSC). The Rural Coordination Centre of BC works to enhance rural education in British Columbia and advocates to improve the health of rural BC residents.

Working at the direction of the JSC, and in collaboration BC’s health authorities, post-secondary institutions, practitioners, and rural communities, RCCbc identifies gaps and overlaps in rural services throughout the province and creates initiatives to address shortfalls. It works to increase and sustain recruitment and retention of rural healthcare professionals to BC and to provide high quality, in-community healthcare to rural British Columbians. The Joint Standing Committee on Rural Issues is a BC-based entity that includes representation from the Doctors of BC, the Ministry of Health, and health authorities. The JSC advises the BC Government and the Doctors of BC on matters pertaining to rural medical practice and develops programs and policies for BC’s rural physicians.

Projects That Benefit Rural Moms & Their Caregivers

The Rural Obstetrics Network

The Rural Obstetrics Network is being established to support rural BC maternity care providers (GPs, specialists, midwives, nurses) in their pursuit of providing sustainable and rewarding obstetrical care within their rural communities.

The program’s mission is to develop and maintain a collaborative community, whose purpose is to support rural maternity care providers (GPs, specialists, midwives, nurses) in their pursuit of providing sustainable and rewarding obstetrical care within their rural communities.

Guiding Principles

- Collaborative

- Interprofessional

- Intersectoral

- Sustainable

- Proactive

- Community-oriented

- Evidence-directed

- Strategic Directions

- Establishment of a robust and sustainable network of rural obstetrical care providers;

- Support sustainable, patient-centred, collaborative rural obstetrical practice;

- Develop a mechanism for open, proactive and responsive communication while providing a voice to rural obstetrical care providers to decision-making bodies.

The North Island Project

The North Island Project began with the goal of creating a patient Decision Aid to help women decide where they should give birth (in Port McNeill’s hospital or down island). After spending time in the community speaking with women and other community members, it became clear that local healthcare providers needed supportif they were to continue to provide services.

Area women gave voice to the challenges they face in having to leave the community to give birth. It is often difficult to arrange transportation, and it becomes challenging to travel if there are other children in the family. For many families, it is too expensive for partners or other family members to travel down island with them, and the whole travel experience can make women feel very anxious.

Leaving the community also means women and families have to find a place to stay to wait until they go into labour, and again for a few days after they have had their baby. This can be difficult as women do not know how long they will need to be out of their community.

Project Context

Adverse outcomes are common results of closures or downgrading of rural health services, as evidenced in BC, elsewhere in Canada, and internationally. The loss of local maternity services and subsequent need for women and families to travel for care has resulted in poorer maternal-newborn health outcomes, and a number of social challenges associated with leaving the community and dissociation from family ties and larger community social supports. Women often have to leave home several weeks before their babies are due, and are away from home for a substantial period of time while they wait to have their babies.

Aim of Project

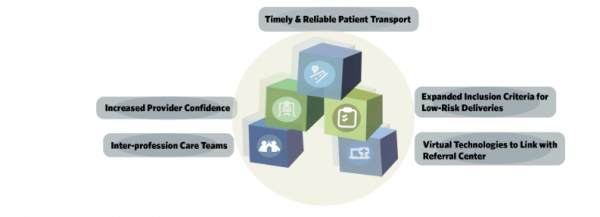

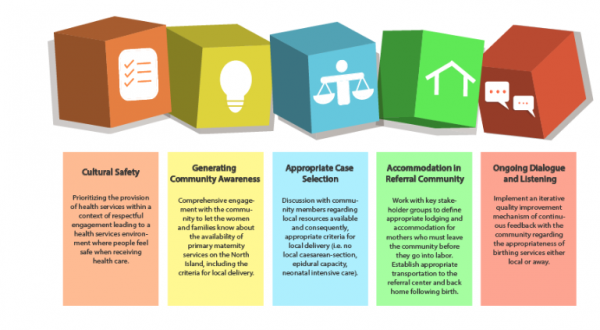

A gap currently exists between system imperatives of birth ‘closer to home’ and health service supports that enable such care. How best to support small rural maternity services, enabling them to provide excellent, high-quality and sustainable maternity care, as an open question. One that had led to a North Island feasibility analysis for each of the Building Blocks for Sustainable Maternity Care (depicted below), in order to further understand how to best support rural maternity care in remote Vancouver Island communities, and across rural British Columbia.

Dr. Granger Avery, past president of both the Canadian and BC Medical Associations, is a long-time Port McNeill-based physician.

Building Blocks for Rural Maternity Care: Working with Communities

The plan is to engage in a feedback loop at every phase in the data gathering process, involving both the local community and the local and referral care provider team to ensure community values and best clinical practices are appropriately captured and summarized. All while continuing an intensive engagement with communities, including First Nations, other key community stakeholders, administrators, and care providers to reflect community priorities.

First Nations Health Authority

The First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) is the first province-wide health authority of its kind in Canada. In 2013, the FNHA assumed the programs, services, and responsibilities formerly handled by Health Canada’s First Nations Inuit Health Branch – Pacific Region. FNHA’s vision is to transform the health and well-being of BC’s First Nations and Aboriginal people by dramatically changing healthcare for the better.

The FNHA is responsible for planning, management, service delivery, and funding of health programs, in partnership with First Nations communities in BC. Guided by the vision of embedding cultural safety and humility into health service delivery, the FNHA works to reform the way healthcare is delivered to BC First Nations, through direct services, provincial partnership collaboration, and health systems innovation.

Services are largely focused on health promotion and disease prevention, and include:

• Primary Health Care

• Children, Youth and Maternal Health

• Mental Health and Wellness

• Communicable Disease Control

• Environmental Health and Research

• First Nations Health Benefits

• eHealth and Telehealth

• Health and Wellness Planning

• Health Infrastructure and Human Resources

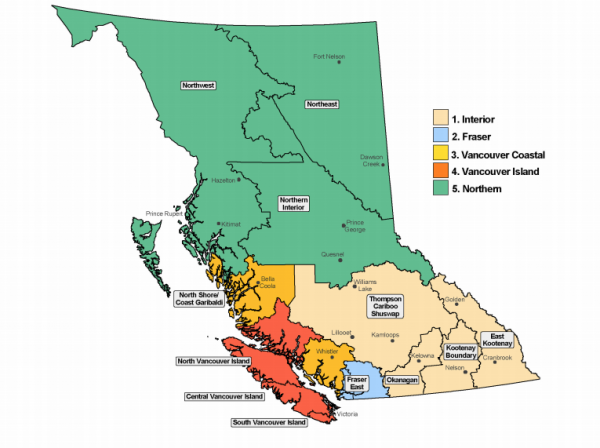

FNHA regions

A unique governance structure

The First Nations Health Authority is part of a unique health governance structure that includes political representation and advocacy through the First Nations Health Council, and technical support and capacity development through the First Nations Health Directors Association. Collectively, this First Nations health governing structure works in partnership with BC First Nations to achieve a shared vision.

FNHA’s work does not replace the role or services of the Ministry of Health and Regional Health Authorities. The First Nations Health Authority is designed to collaborate, coordinate, and integrate respective health programs and services to achieve better health outcomes for BC First Nations.

Primary Care Networks

Across BC, divisions of family practice and health authority and community partners are working to establish primary care networks (PCNs).

A PCN is a clinical network of local primary care service providers located in a geographical area, with patient medical homes(PMHs) as the foundation. A PCN is enabled by a partnership between divisions of family practice and health authorities.

In a PCN, physicians (via patient medical homes), other primary care providers, allied health care providers, health authority service providers, and community organizations work together to provide all the primary care services a local population requires. Together, they:

- Enhance patient care using a team-based approach to care;

- Support each other and work to their strengths;

- Further link patients to other parts of the system, including the health authority’s specialized community services programs for vulnerable patient groups (e.g., frail elderly, mental health and substance use);

- Collectively increase a community’s capacity to provide greater access to primary care for people without a primary care provider.

Participation in a primary care network enables a patient medical home to operate at its full potential.Patients in a PCN get access to timely, comprehensive, and coordinated team-based care, guided by eight core attributes:

- Access and attachment to quality primary care;

- Extended hours;

- Same day access to urgent care;

- Advice & information;

- Comprehensive primary care;

- Culturally safe care;

- Coordinated care;

- Clear communication.

When participating in a PCN, family physicians can:

- Get what they need for patients quickly and conveniently from an array of services in the community;

- Provide optimal care for patients with the support of teams, allied health care providers, and easily-accessed health authority services;

- Access expanded services for vulnerable patients and those with complex health conditions.

A PCN and patient medical home (PMH) are mutually dependent:

- By expanding and improving access to services for patients, the PCN enables a PMH to operate at its full potential;

- As optimized family practices, PMHs are at the core of the PCN.

A patient medical home (PMH) represents the work in the doctor’s office, while the PCN represents system change in the community. A PCN is is governed and supported by the division-health authority partnership with additional support from community partners, through the local Collaborative Services Committee (CSC) or in some cases, a division’s PCN Steering Committee.

- Decisions about the local PCN are made collectively by the local CSC partners and are informed by the participants, including physicians.

- Working with their division, GPs are integral in designing and influencing how local PCNs are designed to support patients.

- Physician leadership and division participation is essential to establish PMHs and PCNs as the foundation of an integrated system of care.

Across the province, CSCs are exploring opportunities to establish and support primary care networks, building on other successful local initiatives.

When CSC partners are ready to formally engage in designing a local PCN or PCNs for their local community (or communities), they complete an Expression of Interest (EOI), indicating their readiness to participate.

Once the EOI is reviewed and approved, the CSC is provided with $150,000 change management funding and other supports to complete a Service Plan developed for their local needs.

The CSC is encouraged to focus their first phase of service planning on ensuring patients who do not have a primary care provider are attached to one. Once the attachment gap is narrowed, the focus is on redesigning local services and adding resources to optimize the team-based care approach.

Following approval of the Service Plan, CSCs are provided with funding to begin implementation.

As of August 2018, 11 communities across BC are engaged in planning services for local PCNs. The first wave of communities, soon to move into implementing their plans, includes:

- Burnaby

- Comox Valley

- Prince George

- Richmond

- South Okanagan Similkameen

The next wave of communities includes:

- Fraser Northwest

- Kootenay Boundary

- Pacific Northwest (Smithers)

- Ridge Meadows

- South Island

- Vancouver

In the coming months, other CSCs will submit Expressions of Interest to begin work on PCNs in their communities. GPs are encouraged to contact their local division to participate in planning and designing services for patients in their community.

Summary

While the challenges in providing a high standard of healthcare to all British Columbians are many, there are many initiatives current underway — from CODI to the FNHA to PCNs — that hold tremendous promise.

To the extent these and other initiatives are to be successful, it is essential the public is as well informed as possible. The common thread between every project covered in this report is the crucial role communities — rural and First Nations citizens — must play in project deployment, if desired outcomes, chief among them enhanced healthcare outcomes for rural British Columbians, are to be realized.

Appendix